Although recent history suggests that humans as a whole (or at least their leaders) are perfectly comfortable with the ever-present risk of a global nuclear exchange, individual authors appear to be more ambivalent. Perhaps it’s some unnatural “life wish.” One coping mechanism that appeared over and over in SF written during the Cold War was to suppose that nations allied with one superpower or another could arrange to sit out World War III, thus suffering only indirect effects.

Personally, I find this a bit dubious for a number of reasons, ranging from the unlikelihood of great powers leaving intact valuable cities in their enemy’s backyard to the hints in such texts as The Wizards of Armageddon that the great nations simply lacked the powers of discrimination required to acknowledge during a hasty nuclear exchange that, for example, China would be sitting this war out. Still, dubious precepts can lead to interesting stories, as these five books should show.

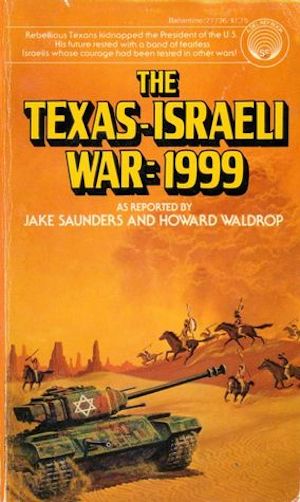

The Texas-Israeli War: 1999 by Jake Saunders and Howard Waldrop (1974)

In 1992, what began as a simple nuclear reprisal by England against the rather implausible Irish-Chinese-South African alliance (who had attacked with LSD!) quickly escalated, drawing all but one major nation into a democidal conflict. The lone exception was Israel. Now it is the only nation untouched by the war; it has become the last remaining industrial nation by default. Land-poor but rich in people and technology, Israelis can be tempted into mercenary service in the shattered nations by the promise of territory.

In North America, embattled separatist Texans take the American president hostage. The US lacks the means to retrieve the president; that job falls to tank commander Sol Inglestein’s mercenary unit. The Israelis are capable of executing the complex rescue plan. What may be beyond them is overcoming the power-crazed American vice president’s efforts to scuttle the mission in order to advance his own career.

If you set out to create the most un-Howard Waldrop-like novel possible, you might very well end up with The Texas-Israeli War. This book isn’t inhibited by any effort at plausibility. It’s like a minor SPI wargame come to life. It is notable in that the American vice president is behaving like a stereotypical evil vizier.

The book is also notable because, despite WWIII and the death of ninety percent of the population, the US still managed to hold both the 1992 and 1996 presidential elections. I could name books in which the US failed at democracy when blessed with its full population.

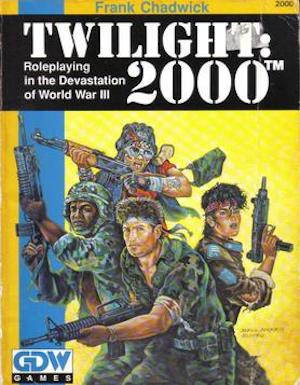

Twilight 2000 designed by Frank Chadwick, Dave Nilsen, Loren K. Wiseman, and Lester W. Smith (1984)

Here’s a non-literary instance of the it-missed-us trope. This near-future tabletop roleplaying game was set in a time after a 1995 Sino-Soviet conflict that—thanks to ambitious East and West German officers seeing a chance for unification in Soviet distraction—escalated into a global conflict. Believing unnecessary war with the Soviets to be folly, France prudently exited NATO. Proximity to the warzone ensured that France would suffer, but neutrality means life in France is “onerous but tolerable,” rather than the living nightmare that is the fate of those in the rest of the world.

French prudence would be great news for player-characters if they were French. However, the game assumes players are NATO forces abandoned deep in enemy territory. As tabletop RPG fans may be aware, France’s judicious caution had a longer-term consequence: as the only major industrial nation remaining, they enjoy centuries of global dominance, as documented in the later roleplaying game, 2300 AD. It is amazing what one can accomplish simply by not dying.

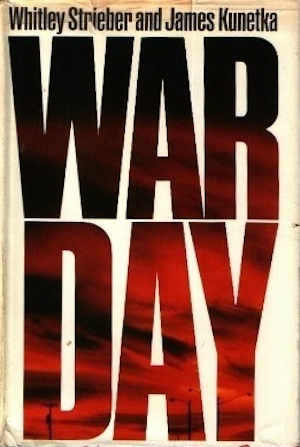

War Day by Whitley Strieber and James Kunetka (1984)

Believing that the impending deployment of the American Spiderweb anti-ballistic missile system would leave the Soviet Union in an untenable situation, the Soviets opted for a pre-emptive limited nuclear strike on US targets. To say the plan did not produce the results desired would be an understatement. Among the unforeseen complications: the secret Treaty of Coventry, in which major NATO nations (and perhaps Canada as well) occupied overseas American bases and sat out the war.

As was the case in Twilight 2000, the Treaty of Coventry would be excellent news for the protagonists…if only they lived in one of the neutral nations rather than the remnants of the United States. The one bright note is that several industrial nations survived WWIII and were able to assist in rebuilding the US. Along lines convenient to the US’s new patrons, naturally.

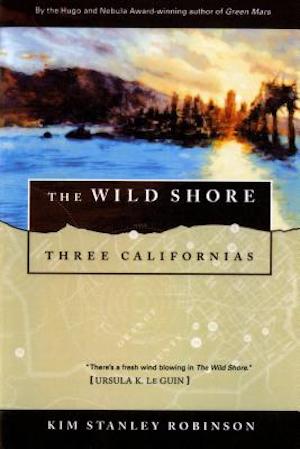

The Wild Shore by Kim Stanley Robinson (19841)

Although but a memory by the time this coming-of-age story begins, the nuclear war that shapes the present in which Henry and his friends live is an extremely odd one: there were only two participants. The aggressor is unknown but the sole victim is clear: the United States, where thousands of cities and larger communities were annihilated by nuclear devices smuggled into the nation. What remains is a patchwork quilt of backward communities that offer teenaged Henry and friends more than sufficient scope to make very poor life choices.

The Soviets are, of course, the main suspect in the murder of the US. They certainly exploit the opportunity presented by the US’s destruction (as do Canada, Japan, and the UK). However, even a nation as notoriously efficient as Russia would be hard pressed to smuggle thousands of nuclear weapons into the US without getting caught. Suspect two is the US itself (being the only other nation with enough nukes). The logistics are far more straightforward, but the motive seems unclear…

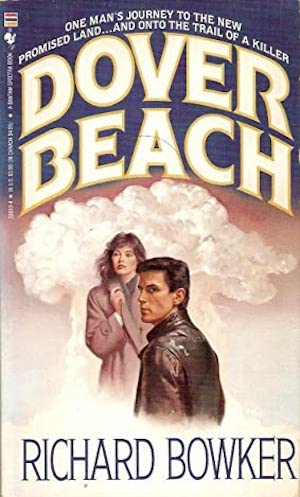

Dover Beach by Richard Bowker (1987)

Post-war America is short on modern amenities. Small wonder that many survivors and their children are obsessed with the relics of the pre-war golden age. Bostonian Walter Sands, for example, is so enthralled by the pre-war Hammett and Chandler classics that he has established himself as a would-be private eye. PIs being in short supply in shattered America, Sands is the logical (possibly only) choice to pursue a case involving clones, scientists, and England’s own version of Operation Paperclip.

The usual methods of avoiding being targeted in a nuclear exchange include such things as judicious chicanery, well-armed neutrality, or not being worth nuking. England in Dover Beach appears to have hit on another method which is simultaneously far more effective than the alternatives and much harder to arrange: pure dumb luck. Either the people charged with annihilating the UK decided not to, or something went comprehensively wrong with the UK attack.

***

Oddly, this seems to be a male-dominated subgenre, at least for works set in and near warzones. I did think of an example penned by a woman—Joan D. Vinge’s Fireship, in which the US sat out the Sino-Soviet War—but there the main purpose was to explain why Americans are global pariahs rather than the universally beloved figures one might expect. I am sure I must be overlooking obvious candidates: feel free to remind me of them in comments below.

In the words of fanfiction author Musty181, four-time Hugo finalist, prolific book reviewer, and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll “looks like a default mii with glasses.” His work has appeared in Interzone, Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis) and the 2021 and 2022 Aurora Award finalist Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by web person Adrienne L. Travis). His Patreon can be found here.

[1]Yeah, it does seem like there were a lot of nuclear war books published in 1984. There have been a lot of nuclear war books published, period. Modern readers used to a rational and stable peaceful world order may find this odd. Many people back then felt that living in a world where Russia and the US provided elderly presidents of dubious rationality with the ability to launch massive nuclear strikes on a whim was at best precarious; they hoped that by writing about the consequences they might convince people to take steps to prevent the worst. Of course, today we know that only about five billion people would die in a nuclear exchange (plus or minus a few billion), which means people now tend to focus on more important things like whether blockchain is the panacea for all problems.